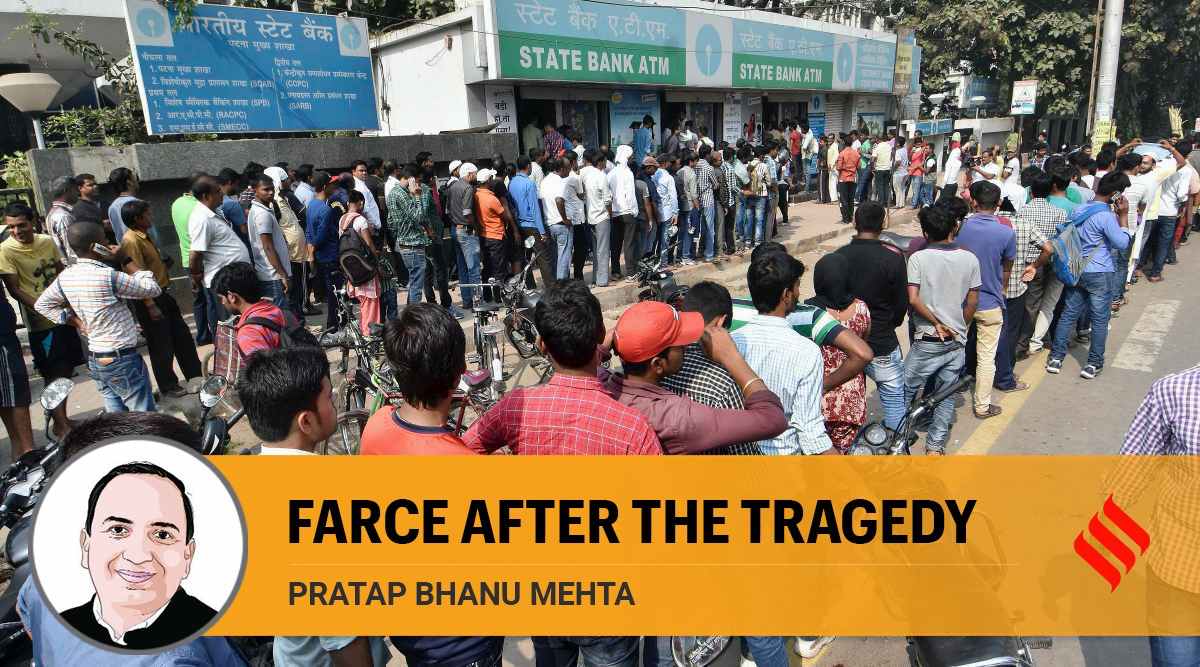

Demonetisation was a shockingly cruel policy enacted under false pretences. It did not achieve any of its stated objectives: A cashless economy, a revenue bonanza for the government, cleaning the system of illicit money, or stopping terror finance. It inflicted needless suffering and made fools of citizens, who willingly acquiesced. But the tragedy was followed by an institutional farce. The Supreme Court evaded pronouncing on the legality of the measure for six years. Now it has, as was widely expected, upheld the legality of demonetisation in a 4-to-1 decision. But even farce can sometimes have lasting institutional consequences. In this instance, it will depend on whether we heed the warnings of the dissent.

Keep in mind one larger context. Independent institutions are meant to act as checks and balances on government. But it is a pipe dream to think that our understandings of what constitutes independent action, or the powers that we ascribe to these institutions, can be drawn independently of political judgment. Sometimes people who normally worry about the power given to independent institutions because they entrench technocratic and elite power at the expense of mass legitimation, will change their positions when faced with a government they don’t like. Often our views on the powers of an institution are also not straightforwardly a matter of statutory interpretation as they are judgments of comparative trust. A lot of people put up with the collegium system, for instance, not because of its statutory underpinnings. It is that, as a matter of prudence, they trust judges a bit more. Often the formal powers of an institution are no predictor of its willingness to act independently.

Read | SC upholds demonetisation, says there was consultation between Centre, RBI for six months

Read | SC upholds demonetisation, says there was consultation between Centre, RBI for six months

In the case of central banks, this challenge is even more acute. We should not pretend that currency decisions do not have a political dimension to them. In this case, the RBI Act was not designed for an unprecedented policy measure of this kind. It was designed for what might be called technical demonetisations, not the wholesale withdrawal of currency. So the debate over whether the RBI’s power to demonetise “any” series implies “every” series has to be seen in this context. Section 26 of the RBI Act also envisages that any demonetisation must formally be initiated by the RBI itself; it cannot be at the direction of the government. This power makes sense for technical demonetisations. It may be disabling in cases like hyperinflation or a national exigency which the government has to manage. The current letter of the law, in this sense, is not totally adequate for the full range of exigencies that could arise. If it is read as giving the RBI the veto in all situations, it is giving it excess power. In this case, given the way the law is framed, there is no pure legal position that can completely reconcile the important values of the RBI’s powers and democratic accountability.

Demonetisation, if it is to be carried out, has to be a sovereign decision. It cannot be an RBI decision. Nor is it clear that you ought to, in principle, deprive the sovereign of this power. It is a different matter that it should not have been exercised in this instance. Nor is it clear, as the dissent suggests, that Parliament could have been involved in a currency decision of this kind; involving Parliament ex ante would make the decision impossible. Secrecy was necessary to this decision. The answer to the risk of executive impunity has to be Parliament. But in this case, post facto political and administrative accountability matters. Parliament has manifestly failed to exercise it.

The demonetisation decision pushed the boundaries of constitutionalism to the edge. It can be argued that the legality of the policy need not be entirely judged by its success; it is not unconstitutional to take horrendous policy decisions. But this does not mean that there is no scope for fixing some administrative responsibility. The importance of Justice BV Nagarathna’s powerful dissent is not the conclusion. It is that it tries to affix administrative responsibility and does not let officials hide behind the smokescreen of statutory interpretations. The need for fixing this responsibility is even more if you happen to think that this is a sovereign decision. Her dissent asks the right question: What was the Board of the RBI doing in all this?

Most Read 1Chandrayaan-3 mission: Dawn breaks on Moon, all eyes on lander, rover to wake up 2As Indo-Canadian relations sour, anxiety grips Indian students, residents who wish to settle in Canada 3Karan Johar says Sanjay Leela Bhansali did not call him after Rocky Aur Rani: ‘He’s never called me but…’ 4Gadar 2 box office collection day 40: Hit by Shah Rukh Khan’s Jawan onslaught, Sunny Deol movie ends BO run with Rs 45 lakh earning 5Shubh’s tour in India cancelled: Why is the Canada-based singer facing the music?Must Read OpinionsTransition to new Parliament building: The infrastructural nationalism is symbolic of our timesSale of ‘The Story Teller’ and the defiance of Amrita Sher-GilWomen’s reservation Bill – finally, a House of equalityClick here for more

It is very clear from all accounts that the RBI Board was handed a fait accompli that it was in no position to apply its mind to and it abdicated all responsibility. We can debate whether the Board was in a position to resist signing the demonetisation resolution. Perhaps it felt that it was giving due deference to a democratically elected sovereign. For a moment, grant this. But even then, to not put on record its concerns and objections, to not ask for evidence for the government’s decision, was an astonishing dereliction of duty. The value of her dissent is greater even if you don’t agree with her final position on the legality of the notification. Her dissent points to an obvious fact. If you want accountable institutions, the formal allocation of powers is not the only issue. What matters, ultimately, is the conduct of officers. Even if they could not stop a decision they could have held the government to account and their testimony could have been part of a retrospective chain of accountability.

The majority decision is egregious in this context. It is a disturbing decision not for upholding the legality of the notification. It is a disturbing decision because it does a total cover-up job. It takes the government’s claims at face value (even the dissent gives the “intentions” of the government a clean chit) it refuses to force even retrospective transparency on the chain of reasoning that led to this decision, and it converts the RBI Board’s dereliction into some kind of constitutional high principle, where it miraculously co-produces the decision with government. It licenses total administrative impunity.

Also ReadWill reservation really help Indian women?Pratap Bhanu Mehta writes on new Parliament: India’s age of ambitionValues Kota imparted: Anxiety and building a future on a butchered presentWith G20-IMEC plan, the global order shifts to Eurasia

Justice Nagarathna is astutely pointing out that things like consultation or application of mind can’t be proforma exercises where the RBI Board simply ticks off a box by signing a resolution in a few minutes. Ironically, the shoddiness of the majority judgment’s reasoning enacts the very thing Justice Nagarathna is pointing out: The real threat of our democracy is professionals, who are otherwise independent, not doing their professional duty. The lesson from this episode is that independence is never in the letter of the law, it is in the character and conduct of form in the vast chain of accountability in a democracy, from judges to officials, from parliamentarians to citizens.

The writer is contributing editor, The Indian Express