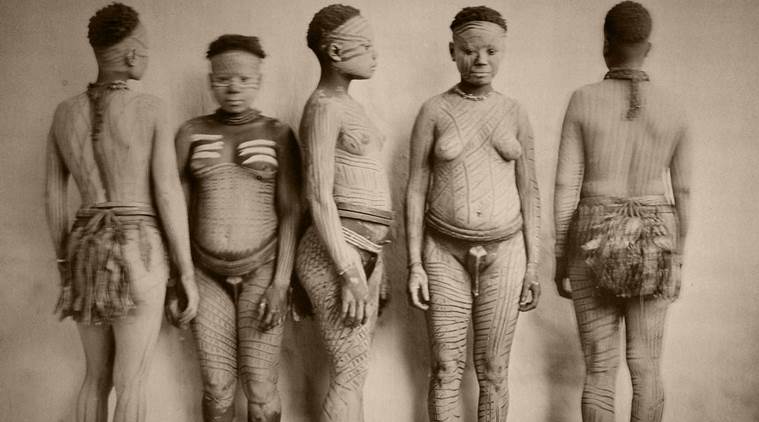

Maurice Vidal Portman, Study from the Andaman Islands, c. 1890. (The British Library, London)

Maurice Vidal Portman, Study from the Andaman Islands, c. 1890. (The British Library, London)

Since the time of its inception in the mid-19th century, photography in India has been an intimate relationship between the outsider and the insider. Born at a time when colonial rule in the subcontinent was at its zenith, the camera was as much an instrument of visual storytelling as it was of administering and controlling a vastly divergent population. Art historian Diva Gujral and art curator Nathaniel Gaskell historicise this relationship, and trace the long history of photographs in India from the time they were clicked by Europeans hungry to understand an alien race, to the way they tell the story of 21st century India.

Their book “Photography in India: A visual history from the 1850s to the present” catalogues the works of 101 photographers. Through the 200-odd photographs featured in this book, they engage with the historical periods in which they were produced.

In a telephonic conversation with Indianexpress.com, Gujral spoke at length about how photography in India has altered and developed over the last two centuries. Below are some excerpts from the interview.

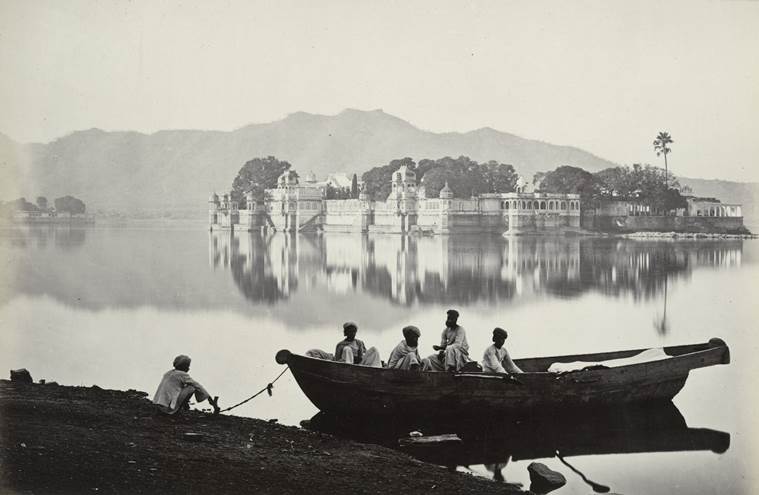

Colin Murray, Jagmandir Island Palace, Udaipur, 1873. (The Hugh Huxley Collection, London.)

Colin Murray, Jagmandir Island Palace, Udaipur, 1873. (The Hugh Huxley Collection, London.)

The camera arrived in India in the mid-19th century, in the heyday of imperialism as you say. In that sense, would you say that the camera was a boon for the country or did it throw across more challenges?

It’s hard to say whether the camera was truly positive or negative. At the time, it could be an instrument of violence, because it was an instrument of documentation of control by the colonial state. On the other hand, as an archivist or scholar working on these photographs two hundred years later, they are incredible historical remnants of a previous social and political order. For instance, the book includes photographs from the album ‘The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay’, which is the first ethnographic album made in the 1850s and published in the 1860s. While the albums are peculiar because they attempt to clinically capture every community in Bombay, they also give shape to the dominant or ‘typical’ characteristics of each community. Other photographs by British civil servants who were photographers really reveal how coercive the photographic process could be, with Indian subjects often visibly uncomfortable in front of the camera. But I think we are all the more rich in our history for these documents because they show us how the colonial lens ordered or categorised the Indian subject. The camera was not in itself positive or negative but it was certainly symptomatic of larger processes of violence and domination.

Did Indians use the medium to express dissent against the colonial powers?

It’s interesting to note how the usage of photography changed over the course of the nineteenth century. Earlier on there were many native members of the Bombay Photographic Society and their practices are not remarkably different from their colonial counterparts because they followed the dominant way of imaging the societal framework that they very much were a part and parcel of. A key photographer involved in ‘The Oriental Races and Tribes of Bombay’ was someone called Narayan Dajee, who was a wealthy Parsee man, whose brother Bhow Dajee was also an accomplished photographer and they were both members of the Bombay Photographic Society.

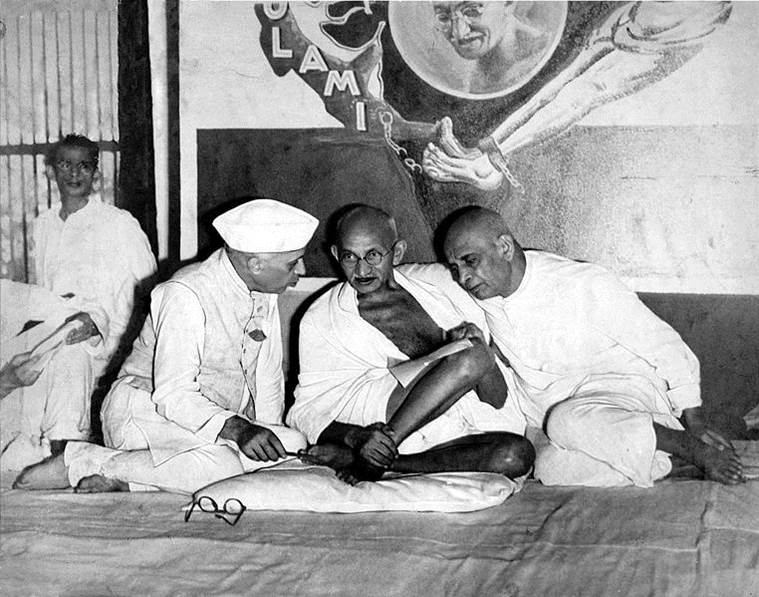

However, things do change by the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, as there are more and more Indian photographers with their own practices. In the wake of Jallianwala Bagh, for example, there is almost a battle that takes place through photographs, with the British trying to capture proof that the natives responded violently and attacked the British after the incident. Meanwhile, there were photographers like Narayan Virkar who took photographs of the survivors of Jallianwala Bagh pointing to the bulletholes in the wall, the only remains of the bullets that killed their relatives. Virkar is a really notable example of an early nationalist photographer who was very invested in capturing the atrocities that Indians were faced with. Kulwant Roy, who followed Mahatma Gandhi around by train in the 1930s, is another photographer of the anti-colonial movement very much from the Indian perspective.

Most Read 1Tiger 3 box office collection Day 1 early reports: Salman Khan actioner eyes biggest Diwali day in Bollywood history 2Pakistani fisherman becomes millionaire overnight after selling rare fish 3India vs Netherlands, World Cup 2023 Highlights: Rohit Sharma, Virat Kohli among wickets as IND defeat NED by 160 runs 4Vidhu Vinod Chopra recalls gifting Rolls Royce worth Rs 4.5 crore to Amitabh Bachchan: ‘He tolerated me’ 5Tiger 3 movie release and review LIVE UPDATES: Salman Khan film trends towards Rs 60 cr earning on day 2, all eyes on if it can trump Jawan records Photograph by Nehru, Gandhi, and Patel by Kulwant Roy (Wikimedia Commons)

Photograph by Nehru, Gandhi, and Patel by Kulwant Roy (Wikimedia Commons)

The camera was an invention of the 19th century, but paintings had existed for centuries before. What difference did the camera bring to the politics of capturing a moment?

The camera has always been associated with truth telling—the earliest notions of the camera, very much from its invention, is that there was a promise of honesty. The idea that the scene before the camera did in fact take place, is very seductive, and it was always assumed to be analogous to a moment in time in a way that a painting couldn’t be. That is what makes it a potent instrument, even though photographs can be so highly staged. When Virkar takes his photographs of Jallianwala Bagh, he has not really photographed the victims or actual atrocity, but he has photographed the bullets in the walls which stand in for the testimonies of the people who died. So there is this idea that the camera can do something for us, it can tell our narratives and provide evidence for the injustices that our held against us.

You write that “photojournalism’s innate and usually successful capacity to sway its audience, deviating from reality to serve needs and biases formed the basis of one of the most pervasive genres in the early to mid 20th century”. Why do you believe that photojournalism is used to serve needs and biases?

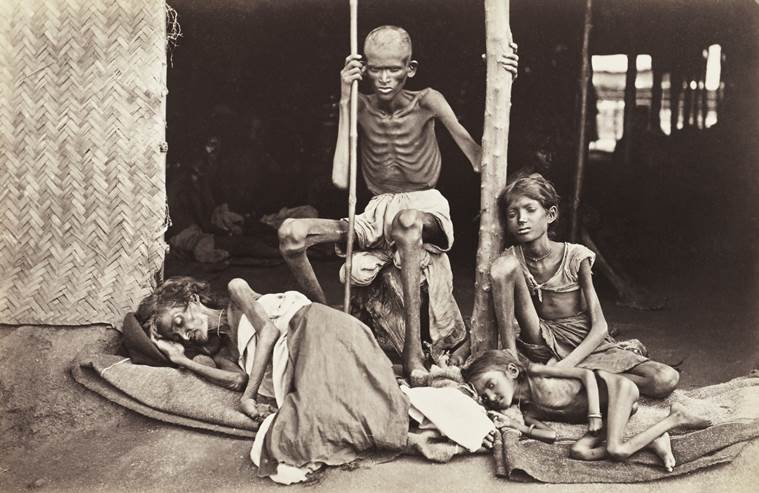

Firstly, photojournalism is perhaps the most textual manifestation of photography. A photograph in a newspaper is inevitably put aside a headline or a caption that fulfills a didactic purpose. In short the text performs instructive work on the image and encourages the reader/viewer to receive the image in an already mediated way. This is also absolutely at work in the colonial world, for example, when photographs of the Madras Famine (1876-78) were intended to perpetuate the idea that the British state should remain in India. The images that are actually indicative of the highest kind of colonial cruelty and mismanagement are completely reframed to send out the idea that British rule was needed because famines still happened here. What happened, in fact, when these photographs were published in Britain, is that the images backfired, and it actually became a moment when people began to wonder why the British were required in Indian given that they had not managed to solve this kind of chaos. But more often than not, I think when photojournalism is put to use it’s almost inevitably with a message. It cannot be neutral because news is never neutral.

Also ReadA brief and crackling history of fireworks in IndiaDecoding why Bengal celebrates Kali on DiwaliA short history of the Sardar Sarovar Dam on river NarmadaHere is what happened in Kedarnath, and rest of Uttarakhand, in 2013 Willoughby Wallace Hooper, Scene of the Madras Famine, 1876-1878. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.)

Willoughby Wallace Hooper, Scene of the Madras Famine, 1876-1878. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.)

In the Indian context, how would you place the camera in the current global socio-political scenario?

I think we are more diffused in the global context, both politically and aesthetically, than ever before. You have photographers coming to India, not to photograph India per se, but for example to photograph injustices that take place in India as well as in the rest of the world. For instance there is a French photographer called Arthur Crestani who did a series called ‘Bad city dreams’, which is about the failure of the vast development projects in Gurgaon and people who get left out of it. It is about class and exclusion and gentrification but it speaks to something that exists everywhere, in the Gulf as well as large parts of South Asia. We are at a point where an older, exotic narrative of India is being transformed into something that is far more universal.

© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd