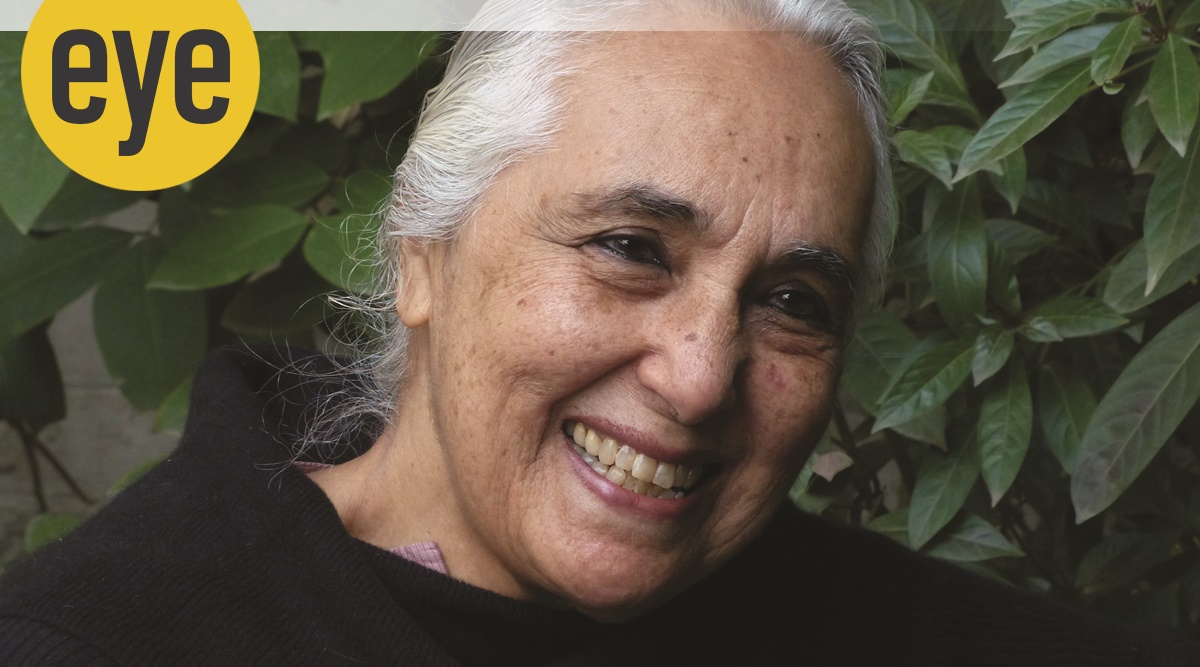

Romila Thapar’s latest book, The Future in the Past (Aleph Book Company, Rs 999), is a collection of essays, new and old, on themes that the historian has engaged with during her long career — the myths around the coming of the Aryans, the centrality of dissent in democracies, the importance of public intellectuals and the insidious attempts by majoritarian governments to control narratives around ‘culture’. These are views that have also put the 91-year-old at the receiving end of criticism and Right-wing vitriol. In this interview, Thapar speaks of the narrow idea of nationalism that can be used to silence dissent, the recent rationalisation of NCERT textbooks and the pushback against Nehruvian India.

How would you say the recent rationalisation of NCERT history textbooks is different in comparison to previous such instances? Could it have been done differently?

It has never happened before that statements and large sections of text in various textbooks in different subjects have been deleted, without viable explanations justifying such deletions. Deletions in accordance with the political ideology of those in authority, rather than the academic quality of the subject being taught, is the only unspoken explanation for this action by the NCERT. In previous times, if any changes were to be made, they were generally marginal. Even so, the author of the book, the committee of historians that had cleared the book and the representative of the NCERT sat together to decide whether anything was to be deleted or added. This time, the procedure adopted to choose the deletions and the rationale remains obscure. Actions pertaining to education these days are haphazard since their concern is not with education but with using education ideologically. The current deletions were done by a few people unconnected with the initial writing of the textbooks. In the past, no changes, however minor, were allowed without the permission of the author. The current deletions have had little to do with the size of the book. These deletions have created an imbalance which has lowered the quality of the history presented. There is no precedent for throwing out passages, pages and chapters from prescribed textbooks, and doing so quite arbitrarily, as is claimed. The pathetic excuse of the NCERT that they were reducing the burden on children carries no conviction.

Good textbooks are not written casually. Their content is discussed in detail. If deletions have to be made, these have to be considered very carefully by a panel of experts. Justification does not lie in attributing the need for deletion to COVID-19 because the curriculum of teaching cannot be hacked in this casual manner. Deleting large sections of history (of the Mughal period) or significant statements (information about Mahatma Gandhi’s assassin or the Gujarat killings) creates gaps that destroy the continuity and logic of history. The original text could have remained to provide historical continuity and a note given that only certain prescribed sections of the text would be examined. This would have reduced the burden on children more effectively than just hacking off sections without a proper explanation.

Scholarship — be it of foreigners studying India or of scholarship critical of India — has become a contentious issue today. Is there a way to engage with this fragility?

It is not scholarship that is so much a contentious issue. What is contentious is the attempt to cut scholarship in order to support a particular ideology, namely the conversion of a democratic secular India into a Hindu Rashtra. Of course we know that it is not social media that determines the historical narrative in history textbooks. It is the writing of qualified professional historians. Throughout centuries in the past, there has been healthy debate, agreement and disagreement, and consent and dissent in India. That is how knowledge proceeded in the past and continues to do so.This process is foundational to many Indian philosophical schools and to rational thinking in our time.

Romila Thapar’s latest book (Courtesy: Aleph Book Company)

Romila Thapar’s latest book (Courtesy: Aleph Book Company)

A fundamental approach to scholarship in Indian thought, as reflected in philosophical texts, requires the discussion of an opinion, the counter-opinion to this and then a possible solution or a continuing debate. It is only now in the last decade that dissent is being silenced. Some academicjournals still carry dissenting views and these are as yet beyond the purview of political control and, hopefully, will remain so.

At the level of school teaching, knowledge in many subjects is being selectively deleted from teaching for ideological reasons, for example, the deletion of the theory of evolution and the periodic table. What remains for the school-going child to learn is a narrow sliver of irrelevantinformation. The only way to push back against this is to insist that knowledge should be open, available and debated, in the texts read at school and in college. And that these should cover all consequential aspects of a discipline. This has been so in the past, and is so in all societies in which education is respected.

Contemporary debates around nationalism tend to overlook the tradition of debate that was intrinsic to India. There is a huge pushback that we see, especially at the university level, where the populist opinion often seems to be that we support your education but will not support your politics. How does one meet that?

It depends in part on what kind of nationalism you are referring to. Nationalism can be all-inclusive, secular and democratic, and a source of encouraging the positive development of a society. Or, it can be narrow and confined to the welfare of only one community in a society, what some call majoritarianism, which negates the positive change in a society as a whole. The first kind of nationalism need not interfere with the tradition of debate in a society, unless it is deliberately used as a form of silencing others — and we know that it has been so used. This happens whenmajoritarianism replaces nationalism. Majoritarianism can easily become — and often does — an authoritative anti-democratic system, negating debate.

Also Read | How the first citizen is connected to the temple of democracy

Education is one of the channels that is used to explain the fundamental change that comes about in a society when the nation-state is established. Those who were formerly subjects now become citizens and with full rights. Our governments have hesitated to establish these rights as theyinvolve major changes, some of which differ from the past, for instance having to share the power of governing. These are necessary changes focusing on democracy and requiring a secular society. The latter two are not just decoration but have to be foundational to a society undergoingsignificant changes. Change of social law and function requires a society that is functioning as a democracy and is secular. Treating democracy and secularism as slogans will not do.

Do you feel that the frequent attacks on public intellectuals as ‘anti-nationals’ or ‘pseudo-secularists’ need a counter or one can ignore them for their ignorance?

But of course these attacks need a counter, that goes without saying. They need a sharp, substantial counter that exposes both the ignorance and ill-will of those that attack. Such attacks on some of us have been constant over the last half-century. Many of these have been made by politiciansand their supporters whose familiarity with history is laughable. Are we supposed to take them seriously? We know who is motivating these attacks and they will not stop until either the show itself comes to a stop or if society decides it can do without them. Their persistence, however, and the space they occupy, is a comment on the kind of society we have become.

In a society where intellectuals and academics are called ‘anti-nationals’, ‘pseudo-secularists’, ‘academic terrorists’ and worse, such name-calling of otherwise accepted people is a sign that society is suffering from ill health. All societies have some degree of ill health, but some have it more than others. We, in our present state, belong to this latter category. The signs are even more depressing when intellectuals are assassinated — as four have been in India in the last decade — simply because they held views that the assassins disagreed with. Violent threats are made day after day by groups that claim affiliation with any among a range of religious organisations.

They demand, for example, the cancellation of lectures by people they do not approve of or discussion of subjects they do not wish to have discussed, with the threat that the gathering will be disrupted and the speaker attacked. Institutions are fearful of such threats, and give in andcancel events. Only a few have the guts to continue and they have to then organise security. How are universities and research institutes supposed to function if they are threatened by any gang that chooses to threaten them?

At another level, there are attacks by trolls on those who express views that are sought to be silenced. No one seems to object to trolls pouring out abuse, some of it quite disgusting, on targeted persons. Do we accept this as normal because we are a tolerant society or are we just too frightenedof those that threaten us? So, we keep quiet and try to ignore it. Most of those thus targeted carry on regardless, as many of us have done. But noticeably, such threats do lead to researchers seeking safer pastures elsewhere. Does anyone in authority care? Is this our definition of acivilised society?

Lawlessness and the abusing of the rights of citizens, be they women, Dalits, Muslims, Christians or anyone else, are not countered efficiently enough to bring down their prevalence. This means that we ourselves as individual citizens have to find a method of self-protection from this abuseand violence. Can we as citizens no longer call upon state protection?

Even if we speak up, help is sporadic, if at all. Perhaps those that control the system are hard of hearing. Should we go back to asking how we defeated colonialism and learn from that? We have to be clear about the kind of society we want and what we don’t want. That clarity is currentlyabsent or not in demand.

The question that needs urgent attention is how do we relocate the lost ethics of our society. How can we re-establish the ethical foundations of our society? I am not referring to building temples and performing religious rituals all over the place, but turning to the real ethic of decenthuman behaviour, that acknowledges the centrality of every human being in a society. This counter has to come from within society, from those of us who endorse the equality and freedom of all. We have to return to being a society that works with at least some ethical norms.

Over the last decade, there has been a pushback against the idea of Nehruvian India. As a young person growing up in India at the time of Independence, how did it appear to you then? How do you look back upon it now?

Most Read 1Chandrayaan-3 mission: Dawn breaks on Moon, all eyes on lander, rover to wake up 2As Indo-Canadian relations sour, anxiety grips Indian students, residents who wish to settle in Canada 3Karan Johar says Sanjay Leela Bhansali did not call him after Rocky Aur Rani: ‘He’s never called me but…’ 4Gadar 2 box office collection day 40: Hit by Shah Rukh Khan’s Jawan onslaught, Sunny Deol movie ends BO run with Rs 45 lakh earning 5Shubh’s tour in India cancelled: Why is the Canada-based singer facing the music?

Independence meant that we were celebrating not just the overthrowing of colonial rule but even more, the establishing of a nation or a nation-state of free citizens with rights: a democratic, secular nation-state. Nehru understood this, as is evident from a couple of things. For example, hisfight to establish adult franchise — much opposed by those who wanted there to be educational qualifications for eligibility to vote and, similarly, the Civil Code that was reduced to the Hindu Code Bill — again opposed by those who thought it was interference with religious rights. The Code,therefore, was limited and not a substantial change to a civil code across society. Some accepted the degree of change that these and similar laws introduced, others felt let down and argued that the government should have gone much further to free society from the shackles of what wasreferred to as ‘tradition’. Implementing the rights of citizens would have to be given primacy, as we all know.

The laws were seen as positive moves in the direction of the new society we wanted, where citizens would have full rights and be free. This has not happened. Changing codes can become cosmetic, or be done to benefit only the few. But as in the past, it has to go through extensive and wide-ranging debate since every community has to undergo some change. It requires a great deal of sensitivity and compassion, both of which seem to be absent in India in current times.

Also ReadEducation Minister launches comic book to sensitise adolescents on holist…From Amitav Ghosh to Perumal Murugan: 15 best books on India'The Hero of Tiger Hill': Book tells story of India's youngest Param Vir …Khalistan movement has gotten nowhere despite Pakistani support, explains…

You have asked me how I look back on it now ? That would require an extensive answer. But let me give a brief answer instead. In the 1940s and linked to the movement for Independence, the IPTA — the Indian People’s Theatre Association – had popularised a poem-song which began with “Yejung hai, jung-e-azadi …. (this is a battle, a battle for freedom)”. And we, as young enthusiastic nationalists, belted it out all over. But today, sadly enough, another song that was sung decades later, and for different reasons, has touched a different sentiment. It opens with the lines, “Thosewere the days my friend, we thought they’d never end ….” Alas, they have now ended. We have to start all over again.