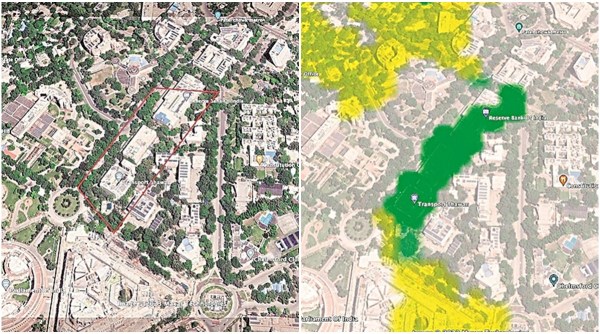

That Lutyens’ Delhi is India’s Capital, the seat of power and home to men and women who run the country, is well known. But what’s not so well known is that the bungalows of ministers and senior officers, even the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) building on Sansad Marg, are “forest” in the official forest cover map.

Parts of the campuses of the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) and All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), and residential neighbourhoods across Delhi are also “forest”, an investigation by The Indian Express has found.

For over four decades, around one-fifth of India has remained consistently under green cover on government records.

Successive governments have not made public the granular data of the country’s forest cover.

The Forest Survey of India (FSI) publishes only the aggregated data in its biennial State of Forest Reports (SFRs) and provides geo-referenced maps for payment on the condition that the “data should not be… given to media”.

In Premium | In chase for growth and carbon targets, questions swirl over forests on paper

In Premium | In chase for growth and carbon targets, questions swirl over forests on paper

A ground verification of parts of the FSI’s latest (SFR 2021) forest cover data offered a glimpse, for the first time, of all that can be labelled forest under the official interpretation of satellite images: private plantations on encroached and cleared reserve forest land, tea gardens, betel nut clusters, village homesteads, roadside trees, urban housing areas, VIP residences, parts of educational and medical institutes etc.

The stretch between RBI and Transport Bhawan on Delhi’s Sansad Marg is a patch of dense forest on the map.

The stretch between RBI and Transport Bhawan on Delhi’s Sansad Marg is a patch of dense forest on the map.

The explanation lies in India’s definition of forest cover.

The global standard for “forest” is provided by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations: at least 1 hectare of land with a minimum of 10% per cent tree canopy cover.

While the FAO does not include areas “predominantly under agriculture or urban land use” in a forest, India counts all 1-hectare plots with 10% canopy cover “irrespective of land use” as forest.

This broad definition, experts say, inflates the country’s forest cover.

Express Investigation | Tracking dubious timber trail & myth of afforestation

“These patches may look green from the sky but they do not support a fraction of biodiversity we associate with a forest. There is no comparison at all in terms of ecosystem services. It’s a crime to mislead national policies with such dressed-up inputs,” leading ecologist Madhav Gadgil told The Indian Express.

Asked about including such areas of limited or no ecological or biodiversity value in India’s forest cover, Anoop Singh, Director General of FSI, declined to comment, saying he was not authorised to speak to the media.

Last week, the office of the Environment Secretary forwarded the queries to the Director General (Forest) who did not respond to emails, phone calls and text messages for comments.

A senior government official, who did not wish to be named, said, “It is not possible to identify different land uses and ownership from satellite images. We are very transparent about the definition we use to map our forest cover. Our definition of forest cover is well accepted by the UN and FAO. Given our population size, it is remarkable that we have made some gains (in forest cover). Every tree, be it in urban areas or in village woodlots and homesteads, is important and is accounted for as such.”

The FSI is not the only one looking at India’s forest cover. Over the years, several independent studies have reported significant loss of forests in India. According to Global Forest Watch, a World Resources Institute platform, India lost 1,270 sq km of natural forest between 2010 and 2021.

Explained | The case for open, verifiable forest cover data

The FSI reported a gain of 2,462 sq km in dense forest and 21,762 sq km in overall forest cover for the same period.

The number game can be traced back to the FSI’s origin. During 1980-82, the National Remote Sensing Agency (NRSA) estimated only 14.10% forest cover in India. “Alarmed, the government formed the FSI (1981) and after a long-drawn bargain (between the two agencies) settled for a forest cover of 19.52% in 1987,” recalled a former ISRO scientist. Even while putting the country’s forest cover at 19.53%, the first SFR (1987) by the FSI noted that only 10.88%, had “adequate (dense) forest cover” and that the situation was “indeed alarming”.

Since then, India’s dense forest cover, according to SFR 2021, has increased to 12.37%. But that includes dense green patches, such as mango orchards, coconut plantations, block plantations of agroforestry etc, outside India’s Recorded Forest Areas.

Forests inside Recorded Forest Area — largely reserved and protected forests — are “basically natural forests and plantations of the forest department”, the government clarified in Rajya Sabha on February 3, 2022.

Only two-third of India’s recorded forest area is forested today. Of that, dense forests, even factoring in the plantations grown by the government, account for only 9.96% of the country.

This loss has remained invisible because of the successive jumps in India’s forest cover since the turn of the century – the increase is often assigned retrospectively, beyond the scope of year-on-year comparison and is justified by advancements made in India’s estimation capability through higher-resolution satellite imagery (see Explainer).

In Delhi, for example, forest cover jumped six and a half times – from 26 sq km to 170 sq km – in 6 years between 1997 and 2003.

Subsequently, the focus intensified on plantations to compensate for the loss of natural forests. Since 2003, according to FSI data, nearly 20,000 sq km of dense forests (40% or more canopy density) have become non-forests. This signifies total destruction of prime forests in an area half the size of Kerala.

More than half of this loss of quality natural forest has been compensated, on paper, by nearly 11,000 sq km of non-forest areas that became dense forests in successive two-year windows since 2003. These are plantations of fast-growing species, say experts, since natural forests do not grow so fast.

On FSI maps, even private plantations on encroached and cleared forest land, The Indian Express found, show up as dense forests. For example, hundreds of hectares were cleared in Assam’s lush Rowta reserve forest in Udalguri district ever since the mid-1990s. Later, multiple tea and rubber plantations came up on the cleared land and now count as dense forest.

On FSI maps, even private plantations on encroached and cleared forest land, The Indian Express found, show up as dense forests. For example, hundreds of hectares were cleared in Assam’s lush Rowta reserve forest in Udalguri district ever since the mid-1990s. Later, multiple tea and rubber plantations came up on the cleared land and now count as dense forest.

Most Read 1Happy Dussehra 2023: Wishes, Images, Quotes, Status, Messages, Photos, and Greetings 2‘SIM Swap fraud’: Delhi advocate receives 3 missed calls from unknown number, loses money from account 3Bishan Singh Bedi passes away: ‘Lost a younger brother, lost a part of my heart’, mourns Pakistan’s Intikhab Alam 4Centre approves voluntary retirement of powerful Odisha IAS officer V K Pandian 5Vishal Bhardwaj recalls Satya days; says RGV used to prostrate before Anurag Kashyap: ‘Anurag had no filters, would say anything’

Similarly, large swathes of tea estates, The Indian Express found, are counted as open forests thanks to the presence of “shade trees” essential in a tea plantation. Significantly, the FAO-UN definition of forest expressly “excludes tree stands in agricultural production systems… and agroforestry systems when crops are grown under tree cover” from forests.

Dr Subhash Ashutosh, Singh’s predecessor at the helm of FSI, said “certain mistakes could occur” during the “vast exercise done in a hurry” every two years.

Also ReadSince 2014, 4-fold jump in ED cases against politicians; 95% are from Opp…Drug menace bigger threat than militancy, we’re going Punjab way: J&K DGP…IE100: The list of most powerful Indians in 2021Veil lifts: Big-ticket defaulters at home have millions stashed abroad

“There was a proposal to do a more comprehensive assessment every five years for better policy inputs while continuing with these biennial reports. It remained on paper. Data transparency is important and we discussed making the maps freely available to the public. But the view was that maps purchased for a price from NRSA could not be given out for free, and that raw data should be shared only for collaborative research,” he said.

© The Indian Express (P) Ltd