One of India’s earliest abstractionists and pioneer of calligraphic modernism in India, Shanti Dave is known for his persistent exploration of the alphabet. Winner of Lalit Kala Akademi’s prestigious National Award for three consecutive years in the ’50s, he also completed several commissions for Air India offices across the globe. Delhi’s DAG is now celebrating over six decades of his artistic journey through an exhibition titled “Shanti Dave: Neither Earth, Nor Sky” curated by Jesal Thacker.

DAG’s retrospective features over 80 works from 1950 to 2014. Would you have done anything differently, in hindsight?

It has been around eight years since I stopped working due to my frail health and eyesight. It was a difficult decision. This exhibition is a true retrospective with works that represent my career but I am certainly not the right person to be judging it. All I can assure (you) is that I never signed any work unless I was truly satisfied, so all my works that are public are the ones that have my complete approval.

You spent a lot of your childhood in Gujarat’s Badapura village before your family moved to Ahmedabad. Do you see any influence of those years in your work?

My memories of the village are rather foggy but I do recall the festivities and how we would often visit the Devi temple. When it rained, I would jump into a pond and swim. Life was rather simple. Ahmedabad was a different world. I had an inferiority complex because I wasn’t fluent in English. I was in my teens when I joined a billboard painter, and soon decided to open my own shop, which earned me decent money. In a way, that was the beginning of my career in art; I studied fonts and techniques.

Untitled (Self-Portrait) Oil on Masonite (Source: DAG)

Untitled (Self-Portrait) Oil on Masonite (Source: DAG)

In 1950, you were in the first batch of students at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU), Baroda. Can you tell us about those years?

I was elated when I first heard about it. Given my family’s financial difficulties, I was dissuaded by Ravi Shankar Rawal (painter) to pursue art but I was adamant. Those were exciting years. I call KG Subramanyan my intellectual mentor and NS Bendre my emotional anchor. I had no money or support system in Baroda, but nothing seemed impossible. I used to eat meagre meals, often shared with friends. The dean of the department, Markand Bhatt, had arranged for a shared temporary accommodation with Jyoti Bhatt, my batchmate. I still recall the night when I saw him working till late, with a table lamp. I realised then that I needed to push myself. From then on, I would only sleep for four-five hours a night and work the rest of the time.

You also began experimenting with medium and material early on.

Osho (spiritual leader) had said if there are repetitions in the path you take, then it is not creativity. I believe in this and have constantly challenged myself at different junctures. Along the way, I have also deliberated on the meaning of art that Manida (Subramanyan) always emphasised on. Once, he took some students to Karelibaug and asked us to draw a tree. After our work was complete, he pointed out how we had failed to capture the underground roots. He told us it was important for our work to be layered and deep-rooted and how we should always be asking ourselves ‘Why am I painting this?’. We were taught to recycle materials. He taught us how to make charcoal by burning sticks of grapes or make crayons with geru mitti. These hacks were particularly useful for someone like me who virtually had no money for art supplies. Over the years, I continued to experiment with mediums, from printmaking to encaustic to watercolours, oil and handmade paper.

Can you tell us about your works for the old Parliament building in the 1950s?

I was still a student at MSU when I got the opportunity to work on the murals for the Parliament through Bendre, who had been approached by GV Mavlankar, the then speaker of the Parliament. We had to make murals depicting the history of India from the Vedic period to Independence. We would get boards, tempera and other supplies from Delhi, and were paid around Rs 2,500 per panel from what I remember. I worked on two panels — one on the Chinese scholars who had travelled to India, the other on Indian astrologers. Shivram Murthy, then director of National Museum, provided the research material.

Untitled Encaustic wax and oil on canvas (Source: DAG)

Untitled Encaustic wax and oil on canvas (Source: DAG)

You frequently travelled in the 1960s to make murals for Air India offices in Frankfurt, New York and Sydney. Did you also use the time to acquaint yourself with movements in Western art at the time?

Air India was a prominent patron and working for them was a wonderful opportunity. We were usually given three-four months to complete a mural. I would often try to do it sooner, and use the remaining time to visit museums and galleries. I studied works of masters like Vincent van Gogh and the social context in which they were produced. I participated in the Paris Biennale and had solos in California, Rome and Frankfurt. The response to my work was heartening.

Your work often centred around the use of Devanagari alphabets. Why is it so? The only time you used words was a series based on the 1965 Indo-Pakistan war…

If you look at linguistics, no alphabet had any meaning till we gave it one. So, for me every alphabet is a composition but does not have any reality of its own. Through my work, I explore the identities we have given them. The series where I was responding to the war is the only time I felt the need to use words such as ‘chetavni (warning)’, ‘hamla (attack)’, because I wanted to directly express my thoughts. These came from news reports — it was painful to witness the horrors of war. We don’t realise how our enemy is someone else’s hero and vice versa; it is people fighting each other.

You’ve been a master of colour but there was a short period in the 1990s when you worked only in black-and-white.

Most Read 1Chandrayaan-3 mission: Dawn breaks on Moon, all eyes on lander, rover to wake up 2As Indo-Canadian relations sour, anxiety grips Indian students, residents who wish to settle in Canada 3Karan Johar says Sanjay Leela Bhansali did not call him after Rocky Aur Rani: ‘He’s never called me but…’ 4Gadar 2 box office collection day 40: Hit by Shah Rukh Khan’s Jawan onslaught, Sunny Deol movie ends BO run with Rs 45 lakh earning 5Shubh’s tour in India cancelled: Why is the Canada-based singer facing the music?

The monochrome series was inspired by Varanasi, and black and white represented the relationship between life and death. It was particularly influenced by one visit to the city when I was travelling with Ambadas and J Swaminathan. We had come across a procession carrying a dead body to the Manikarnika ghat, and realised, how even there, everything was commercial and transactional.

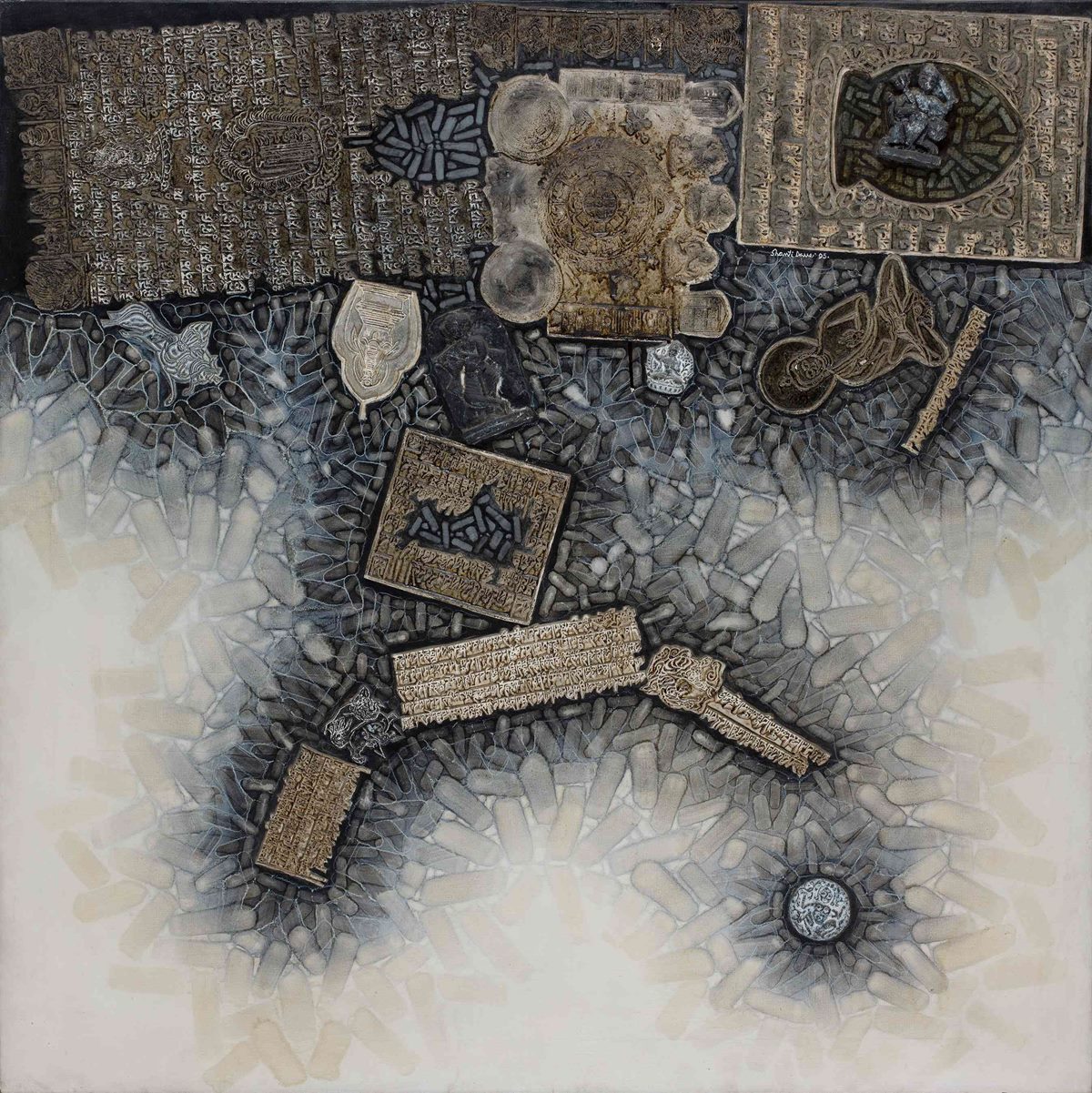

Untitled Oil enamel adhesive and sand on plywood (Source: DAG)

Untitled Oil enamel adhesive and sand on plywood (Source: DAG)

How was your experience working with the government in the ’70s. You were part of the governing body at the Lalit Kala Akademi in 1975.

Also Read‘We were ready to kill it 10 years ago’: Vijay Varma10 things about Chandigarh that will interest youWhy does the mongoose always beat the snake?The life and loves of Mirza Ghalib, the last great poet of the Mughal era

Indira Gandhi, who had studied in Santiniketan, respected art and artists. Within the Akademi, there was a lot of internal politics. (People) wanted to promote associates, but there was the desire to work for the betterment of art in the country.