In the early hours of June 4, 1965, the American president Lyndon B. Johnson stood on the main quadrangle of the library at the historically Black institute, Howard University in Washington, and delivered what would be a landmark speech in the history of Black rights in America. Only two years back Rev. Martin Luther King had delivered the famous, “I have a dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, and about a year back the Civil Rights Act had become the law. Johnson in his address applauded these grand steps taken towards ensuring the freedom and rights of the Black Americans and then went on to declare why he thought these were not enough.

Legal freedom, argued Johnson, was hardly enough to end separation of the races or the unequal conditions experienced by the Blacks. “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, “you are free to compete with all the others,” and still justly believe that you have been completely fair,” he declared.

Later that year, president Johnson issued the Executive Order 11246 which directed government contractors to actively seek out Black candidates for jobs, and called for colleges and universities to recruit more Black students and faculty members. Public organisations as well as non-profit institutions and private companies came under pressure to prove that they were functioning in a non-discriminatory manner by employing more Blacks. It was the beginning of positive discrimination policies in America, or what is more commonly known as affirmative action.

America was hardly alone in experimenting with the policy of positive discrimination towards the goal of uplifting minorities. Decades prior to Johnson’s order, similar sentiments had been brewing far away and at the other side of the world — in India. The history of positive discrimination in India goes back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the development of organised movements by the lower castes, especially in the southern part of India, to effectively cut down Brahmin domination in those regions. In 1921, the princely state of Mysore was the first to institute a system of reserved seats in public service and higher education for ‘backward communities’. Similar policies of reservations soon followed in Bombay and Madras presidencies which were under British rule. Unlike the case in America, positive discrimination was also made part of the Indian Constitution at the time of the country’s Independence, and has, in the years that followed, been revised on multiple occasions.

It is worth noting that affirmative action in both these countries emerged out of similar circumstances. “In the United States and India, affirmative action arose in part because of the blatant exclusion and oppression of specific minorities, particularly Blacks and untouchables, and the dissonance between these principles and stated principles of equality,” explains political scientist Sunita Parikh in her book The Politics of Preference (1997). “In both countries, proponents of affirmative action have invoked the idea of compensation for past wrongs as justification,” she adds.

She also points out that in both these countries affirmative action was introduced without much opposition. Over the years, however, public opinion in both these countries towards positive discrimination policies has turned increasingly hostile. It culminated most recently with the Supreme Court of the United States striking down affirmative action plans at the University of North Carolina and Harvard University on the ground that it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. The ruling was applauded by conservatives, including former president Donald Trump who called it ‘a great day for America’.

In India, although reservation policies have generated much negative sentiments, especially among the elite and have also led to widespread protests, very few Indians and definitely no political party has advocated their termination. What then accounts for the Indian reservation system to be more long-lasting than the affirmative action plans in America?

Affirmative action in America

Perhaps the most striking factor that distinguishes the positive discrimination policies between the two countries is that in America it was never made an effective part of the constitution. Nor was affirmative action drawn up in the form of quotas such as that in India, making the system in America more flexible.

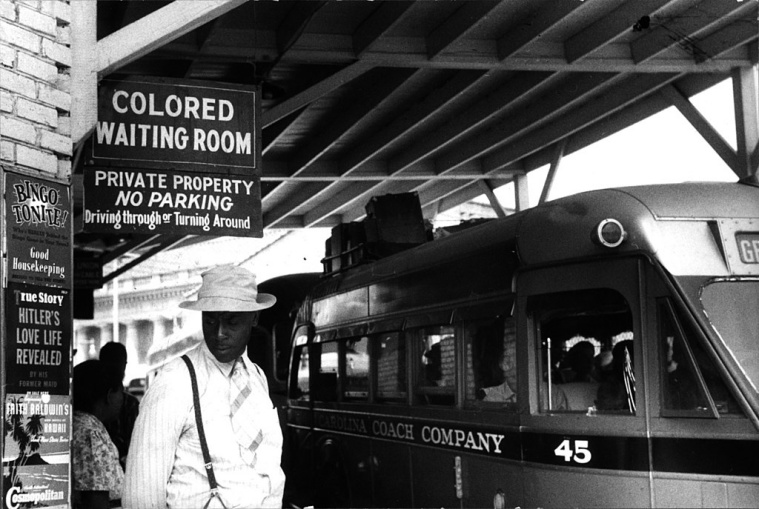

Affirmative action in America needs to be seen in context of the laws of segregation or what was known as the Jim Crow laws that had ruled the southern states of the country for almost a century after the Civil War had ended and slavery abolished in the 1860s. While the 13th amendment to the US Constitution abolished slavery, the 14th and 15th amendments promised equal protection of the law for all residents including Blacks and gave Black men the right to vote. However, the realities of the situation were far from what the law enshrined.

“The Civil War had changed the US Constitution but not the customs nor the feelings,” writes historian Terry H. Anderson in his book The Pursuit of Fairness: A History of Affirmative Action (2004). He explains that after the turn of the century, 17 schools and border states had passed laws that established segregated schools, hospitals, jails and homes for the elderly and differently abled. “Cities enacted local ordinances, so that after sunset entire neighbourhoods could be off limits to Blacks,” writes Anderson. While on one hand the state of Atlanta provided a law ensuring that Black and white witnesses in courts could not swear on the same Bible, in New Orleans, officials went as far as to segregate Black and white prostitutes in red light districts.

Sign for the “colored” waiting room at a bus station in Durham, North Carolina, May 1940 (Wikimedia Commons)

Sign for the “colored” waiting room at a bus station in Durham, North Carolina, May 1940 (Wikimedia Commons)

Things began to change by the middle of the 20th century, after Blacks played an important role in the two World Wars and several of them had moved from the rural south to the more industrial north. Anderson notes that the two World Wars “made it clear that limiting education for minorities was a national security issue.”

“America needed literate young men for combat; training 150,000 Black recruits to read and write during the war demonstrated that minorities could be educated to take orders and to give them,” he writes. Thereafter, by the time of the Korean War in the 1950s, the Supreme Court had started ruling against Jim Crow laws such as those refusing admission of Blacks into professional and graduate schools as well as those ensuring segregation in public buses.

The most important piece of jurisdiction during this period though was the Civil Rights Act of 1964, championed by president Johnson and passed by both houses of the Congress in the wake of the assassination of president John F Kennedy. This Act, which was based on the Equal Protection Clause of the constitution, outlawed all forms of discrimination in American public life.

Soon afterwards, president Johnson issued a number of executive orders directing both public and private offices to employ more Blacks.

President Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Wikimedia Commons)

President Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Wikimedia Commons)

But it was Johnson’s successor, the Republican president Richard Nixon, who is often credited with bringing about the most firm policy in affirmative action. For it was Nixon who for the first time sanctioned goals and time frames for razing down barriers in minority employment. The Philadelphia plan of 1969 required Philadelphia government contractors in six different trades to set aside certain percentages for hiring minorities or risk losing valuable government contracts.

Affirmative action policies were expanded under president Jimmy Carter. In 1977, the US drew up a legislation stipulating that 10 per cent of all federal government construction contracts be kept aside for minorities.

By the 1970s, the universities started chalking out plans for affirmative action. In this case though, there were no executive orders in place to mandate universities to engage in positive discrimination. As economist Thoma Weisskopf writes in his book, ‘Affirmative Action in United States and India: A Comparative Perspective’ (2004) , “such practices were undertaken voluntarily by educational leaders and administrators, in a political climate resounding with calls to reduce racial and ethnic inequalities.”

“They chose this as a means to expand diversity and admit a wider range of students,” says Parikh. However, not all universities follow this as a rule. “Most universities are not that selective in admitting students. But some of the most prestigious universities have many more applications than they can admit,” says Parikh. “So the affirmative action fight is primarily restricted to this very top level of colleges.”

Then there were the Supreme Court rulings which made it possible for the universities to carry forward affirmative action plans. Throughout the 1970s, several opponents challenged affirmative action in the courts but the Supreme Court kept ruling against them. The most important among them was the Allan Bakke case. In 1978, Bakke had sued the University of California at Davis Medical School for denying him admission even though his qualifications were greater than several of the admitted Black students. In a highly fractured ruling, the Supreme Court admitted that it was unconstitutional to have racial quotas, but also said that race can be one of the criteria in admitting students so as to promote diversity. The Bakke ruling was instrumental in enabling educational institutions to continue applying affirmative action preferences in admissions.

Protests against the California Supreme Court’s decision in the Bakke case. (Wikimedia Commons)

Protests against the California Supreme Court’s decision in the Bakke case. (Wikimedia Commons)

It is worth noting that in these early years of affirmative action in the US, the policies were met with very little opposition. “The 1970s were the zenith of affirmative action in America,” says Anderson, adding that “popular opinion polls conducted at that time suggested that two-third of Americans supported affirmative action in the workplace and colleges.”

The outrage over the disproportionate appointment of Black soldiers in the front lines of the Vietnam war along with the emergence of a thriving counterculture in America in the 1960s, played a role in forming public opinion in favour of the Blacks. “This was also the time when Black soul music emerged in the US and the first Hollywood movies with African-American actors hit the screens,” Anderson notes.

Despite the favourable public opinion though, affirmative action was never given a constitutional effect in America, nor did the Congress ever vote on the matter. “The US constitution is much harder to amend,” explains Parikh. “In the US any amendment has first to pass both houses of the Congress and then be approved by three-fourths of the states.” She notes that the last big proposed amendment was the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s to guarantee equal legal rights to all American men and women. It came close to being amended but ultimately failed. Parikh believes that in the case of affirmative action, a proposal to amend the constitution would never have gotten even 40 per cent of the states.

By the 1980s, there was considerable dislike for affirmative action policies in the American social landscape. When president Ronald Reagan came to power he began placing restrictions on affirmative action programmes in government and private sectors. However, he could not completely abolish the policy because by then politicians were fearful of losing out on vote blocs.

Positive Discrimination in India

Unlike the US, the Indian Constitution explicitly provides for affirmative action and there is no controversy over its constitutional validity. Further, while in the US the story of affirmative action effectively spanned about 30 years, in India, its history can be traced back to more than a century.

The history of preferential treatment for minorities in India began with separate electorates for Muslims granted by the British government through the Indian Councils Act of 1909. In the decades that followed the right to separate electoral representation was opened up to Sikhs, Christians and Anglo-Indians as well, although it was only grudgingly accepted by the Indian National Congress.

A round of constitutional reforms were being discussed by the late 1920s and early 30s, whereby Indians were to be given more political representation in the government. Dr. B R Ambedkar, who had risen to prominence as the leader of untouchables by then, strongly advocated for separate electorates for the community. But it was fiercely opposed by Mahatma Gandhi, who was against any kind of separation of the ‘Harijans’ from the Hindu community.

Dr. B R Ambedkar, who had risen to prominence as the leader of untouchables by then, strongly advocated for separate electorates for the community. (Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. B R Ambedkar, who had risen to prominence as the leader of untouchables by then, strongly advocated for separate electorates for the community. (Wikimedia Commons)

Parikh in her book writes that the British acknowledgment of the Congress as the leading political party of India would be less certain if it could not keep untouchables within its fold. She explains that the British were keen on offering reservations and separate electorates to the lower castes in order to break the Hindu coalition being sought by the Congress. “Therefore, Congress leaders had a strong incentive to counter the British offer of separate electorates with similar protection within the Congress fold,” she writes.

Ambedkar and Gandhi’s conflict over the issue has been studied widely and intensively over the years. The two leaders came to a resolution with the Poona Pact of 1932 which promised reserved seats for the depressed classes in federal and provincial legislatures but did away with the demand for separate electorates. The compromise, incorporated in the Government of India Act (1935) established a system of reserved seats for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

Parikh writes that given the antipathy of the Congress, especially Nehru, to reservations in political representations, it would not have been surprising if they had been eliminated when India gained Independence in 1947. However, reservations for SCs and STs were enshrined in the constitution, and through the 1950s and 60s, the policy was extended to public employment and higher education. In the southern states, reservations were carried out for the OBCs as well. Scholars agree that a big reason for the constitutional provision of caste-based reservations in India was because of Ambedkar serving as the head of the drafting committee of the Constituent Assembly.

In the ensuing years, and especially when the dominance of the Congress started falling apart after the death of Nehru, reservation increasingly became a means to attract vote blocs. When the Congress-I party led by Indira Gandhi swept to power in 1971, she introduced extended reservations for OBCs in the north, much to the dismay of the higher castes there. Again, in 1990, when the VP Singh government proposed the implementation of the Mandal Commission report to extend reservations for OBCs, it led to widespread protests in the country. Despite hostility against the policy though, no party in independent India could choose to do away with reservations.

Parikh says that one of the reasons why caste-based affirmative action has been more long-lasting in India is because of the numerical strength of the Scheduled Castes and OBCs which led to greater solidarity, especially in the south. “It meant that the reservations persisted because they were politically attractive,” she explains. “Even though there is a lot of elite resistance to reservations, popular support has always been above 50 percent because so many people were eligible.” One of the reasons why many castes whose status as marginalised groups is debatable have increasingly demanded inclusion in the OBC category is due to the perceived persistence of the policies towards them.

Lawyers, teachers and students during a silent march against Mandal Commission Report in 1990. (Express archive photo by RK Sharma)

Lawyers, teachers and students during a silent march against Mandal Commission Report in 1990. (Express archive photo by RK Sharma)

In the case of the US, where race is the basis of affirmative action, the issue turned more complicated on account of the disparities among the non-white racial groups. “Hispanics and Asians, for instance, are more diverse and their segregation has historically not been as strict,” says Parikh. The increasing migration of Asians, Hispanics and Caribbean and African Black population to the US in recent years has also played a vital role in the shifting attitudes towards affirmative action in the country. “The meaning of affirmative action has changed drastically since the 1960s,” says Anderson.

“The fact that you now have highly visible Asian success stories, even though not all Asians in America are wealthy, undercuts the perception of the need and also creates backlash against policies for minorities,” Parikh adds.

She also adds that the antagonism is more towards the term ‘affirmative action’ and not so much against the idea of diversity. The sentiment about the same becomes increasingly clear when one considers president Biden’s speech soon after the Supreme Court verdict this year: “I believe our colleges are stronger when they are racially diverse….They should not abandon their commitment to ensure student bodies of diverse backgrounds and experience that reflect all of America.”

Further reading:

Most Read 1Chandrayaan-3 mission: Dawn breaks on Moon, all eyes on lander, rover to wake up 2As Indo-Canadian relations sour, anxiety grips Indian students, residents who wish to settle in Canada 3Karan Johar says Sanjay Leela Bhansali did not call him after Rocky Aur Rani: ‘He’s never called me but…’ 4Gadar 2 box office collection day 40: Hit by Shah Rukh Khan’s Jawan onslaught, Sunny Deol movie ends BO run with Rs 45 lakh earning 5Shubh’s tour in India cancelled: Why is the Canada-based singer facing the music?

Sunita Parikh, ‘The Politics of Preference: Democratic Institutions and Affirmative Action in the United States and India’, The University of Michigan Press, 1997

Thomas E. Weeiskopf, ‘Affirmative Action in the United States and India: A Comparitive Perspective’, Routledge, 2004

Also ReadThe many arguments for, and against, abortion rights How Lord Ganesha is celebrated outside IndiaKashmir when India got independence: Neither here nor thereHow Thakurs have dominated UP politics since Independence

Terry H. Anderson, ‘The Pursuit of Fairness: A History of Affirmative Action’, Oxford University Press, 2004