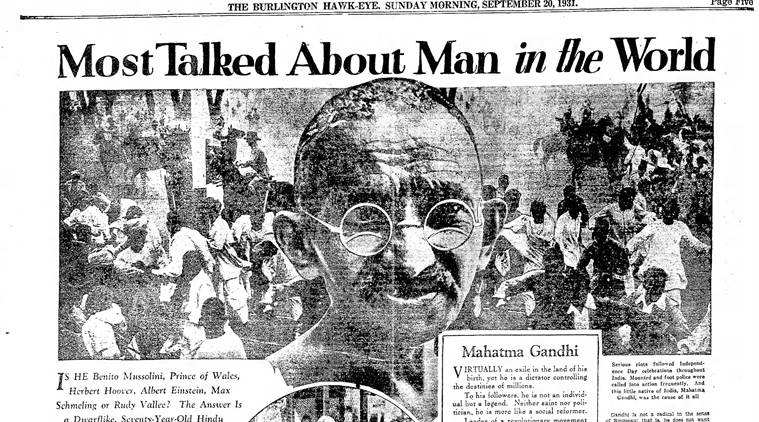

“Is he Benito Mussolini, Herbert Hoover, Albert Einstein, Max Schmeling or Rudy Vallee? The answer is a dwarf-like seventy-year-old Hindu whom millions in India follow with the zeal of crusaders” [The Burlington Hawk-Eye, September 20, 1931.]

“Is he Benito Mussolini, Herbert Hoover, Albert Einstein, Max Schmeling or Rudy Vallee? The answer is a dwarf-like seventy-year-old Hindu whom millions in India follow with the zeal of crusaders” [The Burlington Hawk-Eye, September 20, 1931.]

A significant aspect of Mahatma Gandhi’s strategy in challenging the mighty British empire, involved explaining India’s point of view, publicising the cause of Indian nationalism and influencing the British and later the American public opinion in favour of it to put pressure on the flagbearers of the Raj.

“Between 1905 and 1947, there was a propaganda war between Indian nationalists and British officials for the support of Americans,” writes South Asia historian Leonard Gordon. Until the 1920s, American newspapers heavily relied upon their London correspondents, the British Press and Reuters (which had a mutually beneficial, monopoly agreement with the Government of India for preferential access) for news about India. The news was hence generally from the British perspective and news obfuscation attempts on events that cast the Raj in a poor light, like details of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, usually succeeded.

The US and Britain had a general goodwill due to the presence of many pro-British Americans who sympathised with the British imperial cause and believed in the “white man’s burden”. On one hand, while Britain as a result shared a ‘special relationship’ with the US, on the other hand, another strain of American thinking disapproved of British imperialism — the US itself having been a colony once and a competitor later.

Gandhi first surfaced in the American awareness around 1920 when his first non-cooperation campaign struck a redoubtable blow to the the British raj and since then he was, in Lloyd Rudolph’s words, “revered and reviled”. His ideas of a freedom struggle appeared unfamiliar and exotic to Americans — fascinating to some and threatening to others.

The newsmaking Mahatma of the 1930s

Mahatama Gandhi during his historic Dandi March on 12.3.1930. Express archive photo

Mahatama Gandhi during his historic Dandi March on 12.3.1930. Express archive photo

Gandhi’s iconic Dandi March in 1930 was a watershed moment in directing the western media spotlight on India. The event became a launchpad for sustained, popular American media focus on India and on Gandhi in particular. Indeed it was designed to be such. Media scholar Chandrika Kaul points out that before embarking on the march, and again upon breaking the salt laws, Gandhi had been in touch with the Director of Indian Independence League in New York, directing him to publicise the protest. And so the New York Times published Gandhi’s appeal under the headline, “Gandhi Asks Backing Here: Urges Expression of Public Opinion for India’s Right to Freedom,” in which he exhorted American sympathisers of his cause for a “concrete expression of public opinion in favour of India’s inherent right to independence and complete approval of the non-violent means adopted by the Indian National Congress”.

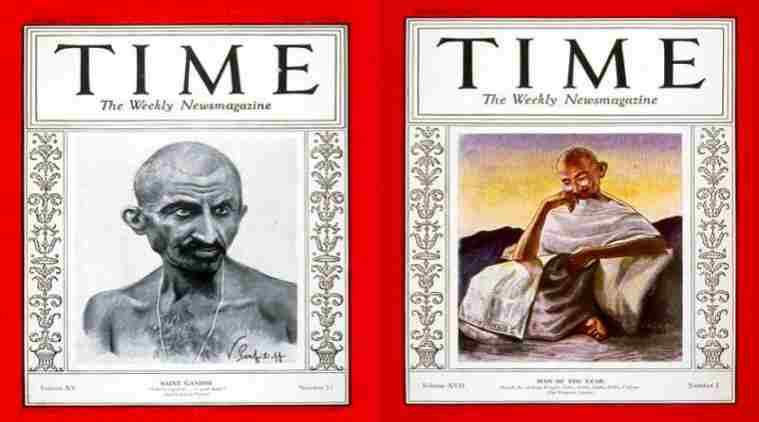

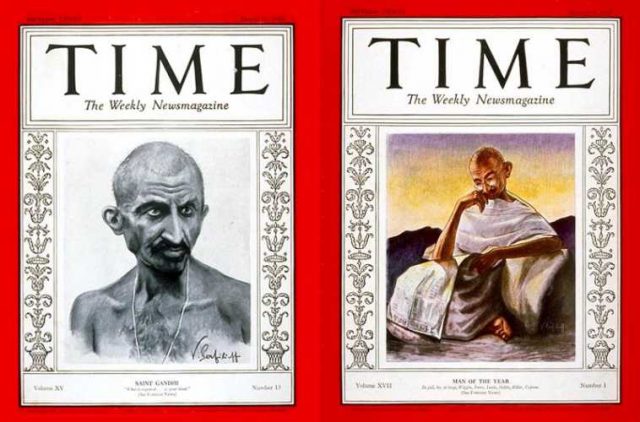

The dramatisation of Indian nationalism in 1930 in the form of Salt Satyagraha prompted the Time magazine to feature Gandhi on his cover, under the title, “Saint Gandhi”. The cover feature titled “A Pinch of Salt” argued that had an English politician in a loin cloth walked 80 miles to London barefoot, “the Englishmen would have thought him mad”. However, as Gandhi “trudged along last week … Englishmen were not amused but desperately anxious.”

Original American reporting on India intensified thereafter, with various newspapers and periodicals such as the Wall Street Journal, Chicago Tribune, Chicago Daily News, Washington Post, Nation, Time etc. along with the agencies Associated Press (AP) and United Press (UP) consolidating their resources and correspondents to that end. This is not to say that all press coverage of India and Gandhi was supportive — the British imperialism also had its champions among American publications.

Gandhi: Time Magazine’s man of the year in 1931.

Gandhi: Time Magazine’s man of the year in 1931.

The following year, in 1931, Gandhi, who was almost unknown in the US until a decade earlier, also became Time Magazine’s Man of the Year. The feature sizzled on the forefront of American press for several days as breaking of the salt law was compared to an iconic event in American freedom movement: the Boston Tea Party. By the 30s, Gandhi had become a permanent nuisance to the British Raj. He emerged in the western world, especially in the US, as enormously newsworthy. In addition to spotlighting his appearance and personality, Gandhi’s challenge to the British imperial juggernaut was given a dramatic treatment akin to an unfolding David and Goliath in many publications.

A number of documentaries and newsreels were made of Gandhi’s visit to England for the second Round Table Conference in 1931 and his activities in India by foreign producers in keeping with the importance of Indian news in general and of Gandhi in particular. “We have recognised from the beginning that Gandhi’s campaign depends to a very large extent for its effectiveness on publicity,” read a GoI Home Office secret memo dated April 2, 1930. “Consequently our policy has quite definitely been to curtail the Gandhi publicity and to do as much counter-publicity of our own as is feasible” (quoted in Chandrika Kaul’s Communications, Media and the Imperial Experience).

It is notable that American journalists and observers, especially those with pro-Raj sympathies were generally specially received and assisted by the Government of India at this point. The efforts of many prominent American journalists in going past this official handling is noteworthy in this context.

Webb Miller and the United Press

Webb Miller was the only foreign correspondent who covered the Gandhian demonstration at the Dharasana salt works. The government of India did its best to keep him away from Gandhi and prevented his cables from going out, but once he realised this, he managed to sneak some of his despatches out via another channel. The United Press copy recounted his eye-witness testimony as more than 2,000 Khadi-clad demonstrators advanced towards the salt deposits on May 21, 1930.

Despite attempts at professional neutrality, Miller’s story of brutality by officers of the Raj against unarmed and fearless demonstrators sullied the picture of the civilised, benevolent Raj looking after poor, unsophisticated Indians painted by writers like Katherine Mayo. The Dharasana story appeared in 1,350 newspapers served by the United Press throughout the world and make the path of nonviolent resistance world famous.

J A Mills – Associated Press

In spite of facilitation and leads from the British, veteran correspondent J A Mills of the AP came to strike a special rapport with Gandhi. He wrote a series of in-depth features and detailed sketches of Gandhi, capturing the unfolding drama and its chief protagonist which were syndicated by newspapers across the US.

Mills also traveled on the same ship as Gandhi on his voyage to England in 1931 for the Round Table Conference and came to develop a close working relationship with Gandhi and the persons accompanying him. He also interviewed Gandhi several times, including what became Gandhi’s first audiovisual interview.

William Shirer and the Chicago Daily Tribune

The commercially successful Chicago Tribune was dominated by Robert McCormick, a managing editor who disliked the European powers and to whom Britain in particular exemplified all that was wrong with Europe. In practice therefore, the paper was widely regarded as anti-British and was known to relish ‘twisting the [British] Lion’s tail’. Though it often acknowledged the benefits of imperial rule, the Tribune was generally supportive of Indian demands for self-government.

Most Read 1India versus New Zealand: Mohammed Shami has mastered the art of bowling out batsmen, like Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis did 2Vishal Bhardwaj thought Kaminey won’t work because nobody was getting along on set: ‘There was so much conflict…’ 3Ganapath box office collection day 2: Tiger Shroff-Kriti Sanon’s dead-on-arrival film fails to crack Rs 5 crore mark after two days 4India vs New Zealand Highlights, World Cup 2023: Virat Kohli’s brilliance takes IND to a four-wicket win 5Leo box office collection Day 4 early reports: Vijay’s film makes the best of first weekend

The late American journalist and author, William Shirer, is best remembered for his expose of Nazism and the Third Reich. However, when he was assigned to India in 1930 by McCormick, Shirer was a 27-year-old correspondent. He was able to establish a rapport with Gandhi early on and became one of the foreign correspondents that Gandhi trusted and valued. Like Miller, he sympathised more with the Indian nationalists led by Gandhi than with the raj. Through his descriptive and compelling prose, Shirer was able to bring to life a world far removed from the experiences of his American readers.

Fine journalists such as these did not just describe, but also performed the hardwork of going beyond the superficial to understand the complexities of the Indian situation. They labored at demystifying Gandhi for their audience through evocative profiles, without flattening out his fascinating, full-of-contradictions personality. The character of Vince Walker in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1983) was a composite one based on these real life journalists.

Also ReadHere is everything you need to know about Indian JewsHere is what happened in Kedarnath, and rest of Uttarakhand, in 2013Why Islamic State in Afghanistan harks on the concept of Khorasan and wha…From Vivekananda to Motilal Nehru: The Indian leaders believed to have jo…

As Kaul puts it, “It was the presence of the American media — unfettered, interested and aware — that ensured that the story of Gandhian nationalism gained a transnational status which, in turn, contributed to make the Civil Disobedience Movement the most formidable challenge yet faced by the Raj.” Significantly, the British raj was helpless beyond a point to censor or repress American journalists, whose nationality served as an immunity of sorts. There could be rejoinders, protests and fuming over certain accounts but the Government of India could could not resort to the same means that Indians were subjected to. That could only be done at the risk of further bad publicity for themselves.

© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd